What is the Cost of Your Information?

Max Gannon discusses how most malware, regardless of the device it's installed on or its method of installation, typically steals information from the infected platform. The focus is on what threat actors do with this stolen information, and what type of information is typically targeted. The article, "How Much Does Your Information Cost?" was posted on Cofense.

By Max Gannon

Regardless of the device it is installed on or how it got there, most malware steals information from the platform it has infected. The question is, what do the threat actors controlling the malware do with the stolen information? We are going to take a look at what kind of information is stolen by some of the top malware families, what threat actors do with the stolen information, and what value the stolen information has. We are also going to briefly cover how Initial Access Brokers (IABs) fit into the threat landscape in relation to what kind of access some of the top malware families pursue. The price ranges used for the information gathered were derived from a number of dark web marketplaces.

Information Collected and Activities

Each of the following malware families has different methods of collecting the information that they steal but the end result is the same; threat actors can recover a trove of stolen data from each computer that they infect. However, the actual prices are so low that, for most threat actors, crime really does not pay well. The following are some highlighted malware families consistently seen in the top 5 over the last year. It is worth noting that each one originally fell into a different malware “type” with QakBot breaking the trend over the years until it became the multifeatured malware that it is today. Emotet is being excluded due to lack of recent activity, but it is worth noting that Emotet’s primary functionality became acting as a malware loader with increasingly less focus on stealing credentials.

QakBot

QakBot began as a relatively straight forward banker with a basic self-propagation component. It has since advanced to the point that, with all plugins loaded, it can act as a fully featured Information Stealer, log keystrokes, perform reconnaissance, spread laterally, load additional malware, and generally act as a Remote Access Trojan (RAT). The Information Stealer plugins are advanced enough that it searches not just installed applications but also system files used to store password hashes. As a result, it quickly attains the level of access needed to be able to sell access to the computer to an Initial Access Broker. In fact, QakBot is well known for consistently providing IABs with access and is particularly known for selling access to threat actors who deliver ransomware.

Agent Tesla Keylogger/Snake Keylogger

Agent Tesla Keylogger and Snake Keylogger are two of the top malware families seen by Cofense, but they have remarkably similar capabilities. In fact, the only significant difference is that Snake Keylogger can also interact with the victim’s clipboard. Otherwise, they are both able to act as a Keylogger, take screenshots, and perform some basic credential recovery from browsers, FTP programs, and mail clients. Given their limitations and general inability to accept commands, these Keyloggers are unable to perform additional actions that would be required to sell access.

FormBook

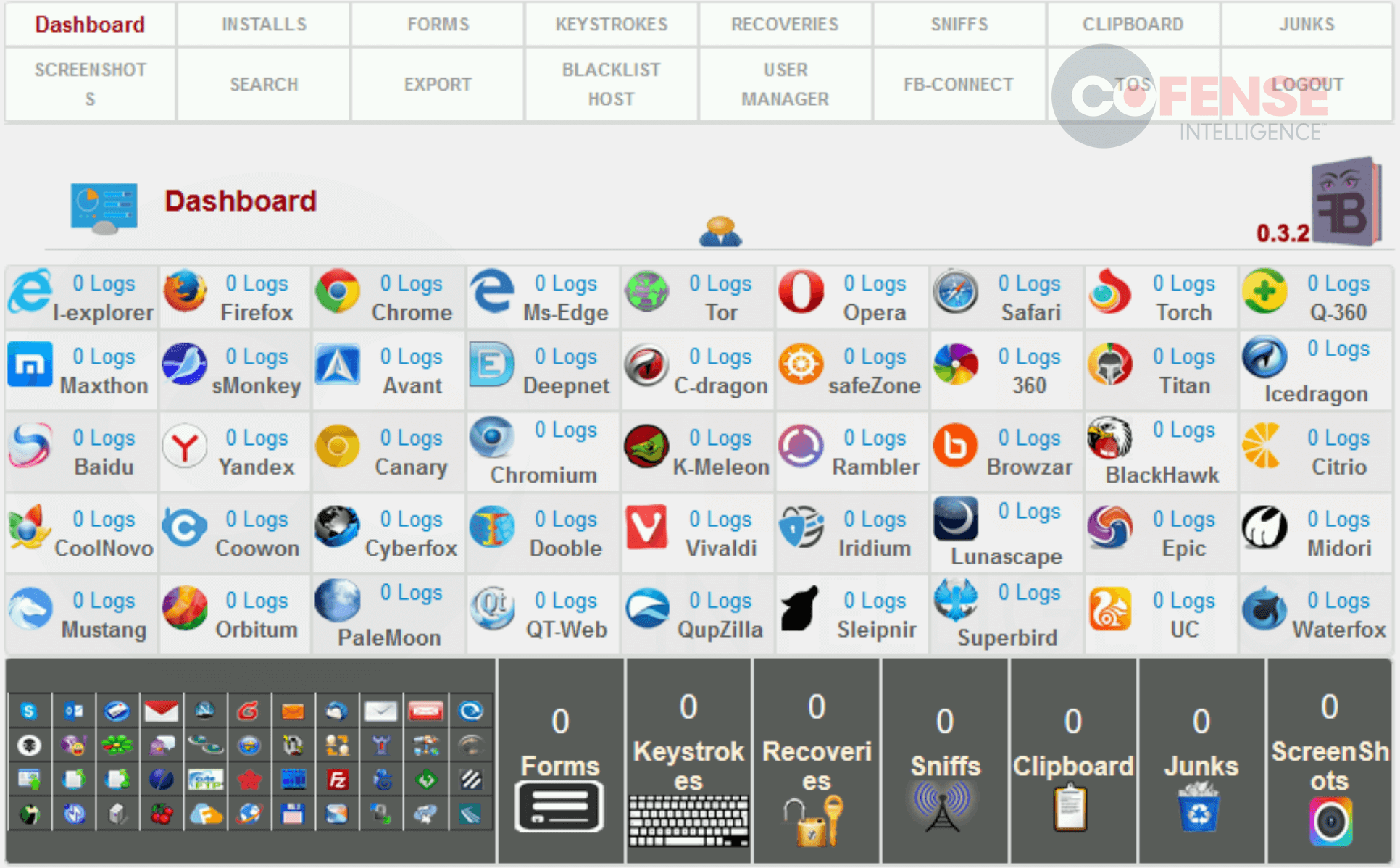

Despite being designed as an Information Stealer, FormBook has a suite of capabilities far beyond what is typical for a basic Information Stealer. FormBook is capable of keylogging, file management, clipboard management, screenshotting, network traffic logging, and password, cookie, and form recovery from browsers. A picture of a FormBook web panel, including the various programs targeted by the stealer, can be seen in Figure 1. Making use of FormBook’s ability to run remote commands as well as download and execute files, threat actors could use a basic FormBook infection to install additional malware and tools, allowing them to sell access to the computer to an Initial Access Broker.

Figure 1: FormBook web panel displaying tools and targets.

The Remcos RAT epitomizes the modern Remote Access Trojan with its arsenal of invasive tools. With capabilities ranging from keylogging and screenshotting to commandeering the user's camera and microphone, it's a Swiss Army knife of cyber intrusion. Its potency is magnified by the fact that it grants malefactors unfettered control over the infected computer, paving the way for Initial Access Brokers (IABs) if the infiltration is executed with finesse.

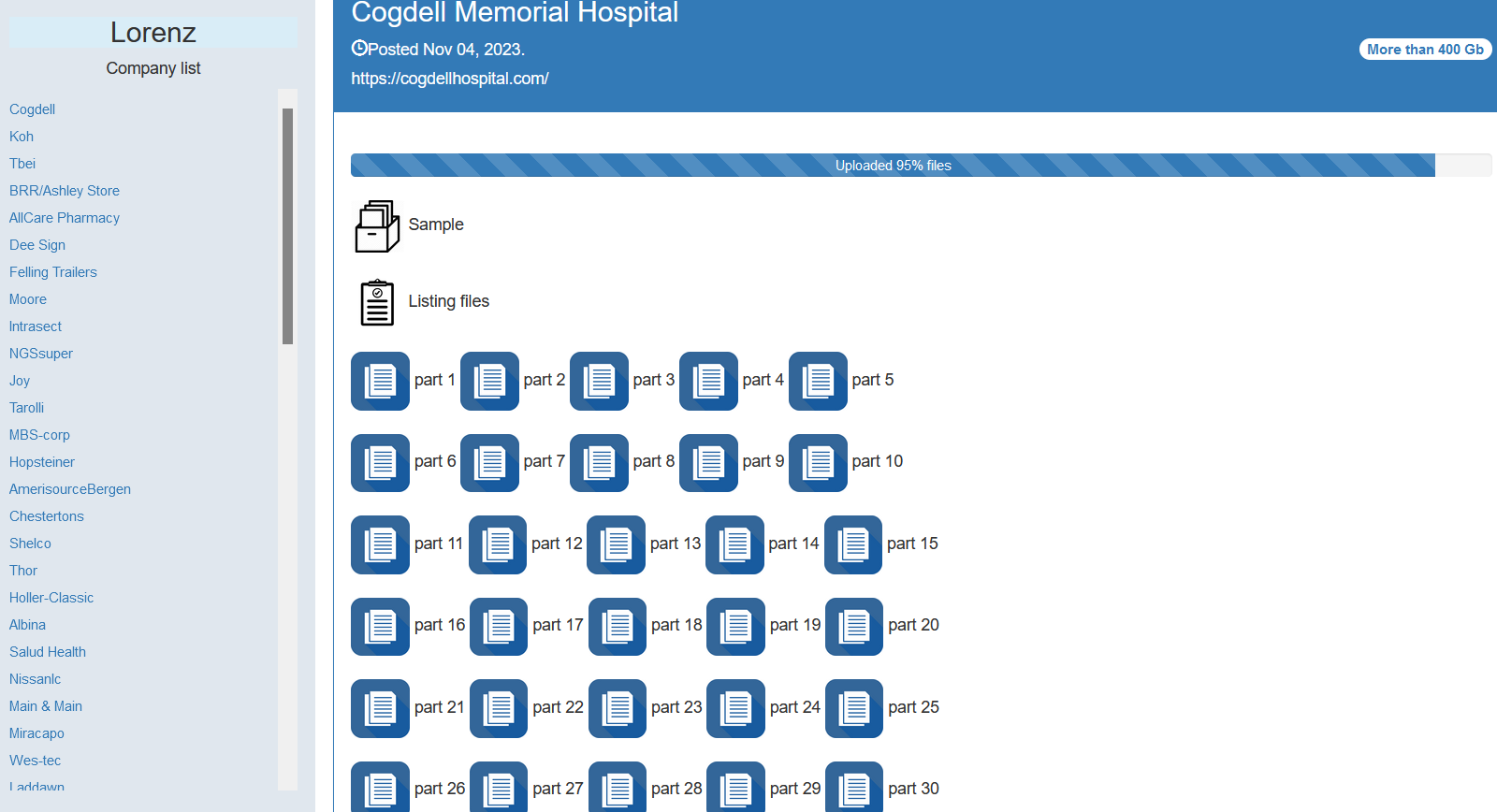

IABs are the dark web's brokers of digital intrusion, peddling the keys to compromised systems at a premium. Their wares originate from the digital footprints left by malware operators like those behind QakBot. The spectrum of access types varies, but the crux lies in the malware's role in establishing that initial foothold, which can then be leveraged for nefarious ends, such as ransomware attacks or data theft.

The lucrativeness of these digital break-ins is not lost on the cybercriminal community; access credentials can fetch sums stretching into the hundreds of thousands, depending on the stature of the breached entity. Conversely, access to individual personal systems might be auctioned off for a mere pittance. Industry connoisseurs estimate the average market price for initial access hovers just shy of $3,000, a significant uptick from the paltry $1.5 typically fetched by full botnet logs.

The commodities of the cyber-underworld aren't limited to access alone; the information filched during breaches is a hot ticket item. This data, often unvetted for authenticity, is hawked in bulk across shadowy online bazaars. Buyers, operating on a system of precarious trust, are tasked with verifying the stolen data's validity—a process that, while seemingly ripe for abuse, operates on an unspoken honor code amongst thieves.

Credit and debit card details—complete with full personal addresses and auxiliary data—command prices ranging from $10 to $30 apiece. Factors like the card's origin, the richness of accompanying information, and the card type all play into pricing variations. Market dynamics, seller reputation, and the volume of cards in a batch also influence cost, with refunds typically available for defunct cards or inaccurate data. However, these price points are mere snapshots from a vast and variegated dark market landscape, with specialized outlets likely offering both higher and lower rates.

Full Profile With SSN

A person’s full profile, including their SSN (or regional equivalent), address, etc. can go for anywhere from $2 to $5 per person and is often sold in batches of several hundred at a time. Refunds are typically available if the information is inaccurate. A threat actor can buy a person’s full profile and essentially ruin their life and credit score for less than stolen streaming service credentials. An image of one store selling full profiles in bulk can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Dark web marketplace selling bulk full information bundles.

Credentials for online retail accounts can be as cheap as $0.10 or as expensive as $5 each, with bulk sales being the norm. This data is frequently sold in large batches, often by the hundreds, reflecting the inconsistency and risk inherent in these transactions. In the murky trade of stolen login information, refunds are typically not an option, leaving buyers to gamble on the validity of the credentials they purchase.

When it comes to online banking login details, prices fluctuate dramatically, hinging largely on the bank balance of the compromised accounts. For example, a batch of 200 unverified login credentials for a major financial institution might go for as little as $90, with no safety net of a refund should they prove incorrect. On the other end of the spectrum, a single confirmed account with a balance of $458,462 could fetch a steep price of $4,500. In instances like these, depicted in Figure 3, the vendor may offer a refund for incorrect information, adding a layer of security for the buyer in an otherwise insecure and unpredictable market.

Botnet Logs

Another category of information is for Botnet Logs. These are all the information gathered on an infected computer, such as cookies, keystrokes, screenshots, and stored credentials and are typically sold based on network traffic. For example, a compromised computer that has a record of network traffic to a leading financial organization is $30, one with network traffic to a different financial organization is $25, and one with traffic to Target is $5. When these botnet logs are sold in bulk without any checking of their contents, they range from $0.50 per record to $2.50 per record.

Other Information

Other information trafficked on these websites includes credentials to social media websites, license keys, streaming services, small business email accounts, lists of valid emails to spam, and loyalty rewards programs, such as frequent flier miles, for rates like $4 for an account with 8612 miles.

The post How Much Does Your Information Cost? appeared first on Cofense.

![Largest Data Breaches in US History [Updated for 2023]](https://nulld3v.com/uploads/images/202311/image_430x256_654e69df8d469.jpg)